Of all the monstrous creatures, none have ever been treated so poorly as goblins. Although vampires, werewolves, and trickster faeries lend themselves well to eroticization in modern literature and popular culture, goblins remain relatively true to their original depiction: greedy, grotesque, hooked nose fiends who exist solely to deceive good people-typically those of the Aryan variety-in favor of their own selfish gain. But why should every other beast be prone to beauty except this particular breed? Enter Goblincore, a new online subculture determined to prove that beauty really does exist in the eye of the beholder. Rather than prioritizing dainty, sensuous folklore characters like fairies, nymphs, or mermaids, it uses goblins to embrace the strange, queer, and peculiar.

Picture less roses, more dandelion weeds. A soundtrack designed to emulate the ideal atmosphere might feature songs like Hozier’s In The Woods Somewhere and Boys Will Be Bugs by Cavetown. Imagine Over the Garden Wall meets David Bowie’s film Labyrinth. Goblincore emphasizes a sustainable, off-the-grid lifestyle tied with elements of modern spirituality, like green witchcraft and collecting rainwater to harness its energy. From the perspective of such a chaotic, niche, aesthetic, self-identified internet goblins are encouraged to explore their own weirdness through fashion. Key motifs include muted colors, frogs, snails, dirt, worms, and various fungi. Compared to other popular internet cores, aka styles inspired by one specific feature, goblincore chique subscribes to no standard style. Outfits center comfort over capitalism, likely due to neurodivergent and LGBT+ communities at the forefront instead of the background. Because I have both Autism Spectrum Disorder and ADHD, I experience sensory overload daily, making it difficult to partake in most trends since certain fabric textures make me want to hurl myself at the sun. Goblin clothes, meanwhile, cater to accessibility and personal comfort-well loved shirts, old sweaters, trousers, pins, buttons. Basically, unhinged grandma attire.

Goblincore emphasizes a sustainable, off-the-grid lifestyle tied with elements of modern spirituality, like green witchcraft and collecting rainwater to harness its energy.

When most people think of high fashion, goblins may not be the first thing to come to mind.

Even so, Gucci tried to achieve the essential mayhem of the Goblincore look with their controversial Fall/ Winter 2020 collection. The Italian powerhouse advertised high-end, intentionally grass stained jeans, though ultimately failed to meet the mark with the expensive $1200 price tag and haute couture commercialization. The brand’s website defended the designer’s unique artistic decision, stating: “This wide-leg denim pant is crafted from organic cotton specifically treated for a stained-like, distressed effect… Gucci explores new takes on design techniques that blur the line between vintage and contemporary.” Sorry, Gucci. Real goblins stain their own jeans. Disregard labels and luxury. To decipher whether an outfit fits the goblin agenda, one must simply look in the mirror and ask themselves: would Bilbo Baggins wear this on an epic adventure to save the world?

If the answer is yes, then please proceed. Mordor awaits.

Goblincore has become especially favored among the LGBT+, and neurodivergent communities, especially autistic, nonbinary individuals. It’s not hard to see why. The term ugly inherently rebels against predetermined expectations. Ugly has been used throughout history to demonize anyone deemed antithetic to the mainstream majority. The non-white, cisgender, heterosexual, able bodied, neurotypical, Christian. We may never call these outsiders ugly explicitly, yet the foul description persists regardless in the stories we tell about ourselves, especially when an author erases what makes them human. They consequently substitute fiction for fact, stereotype for reality, myth for truth. In the unfortunate case of the goblin, the writer traditionally alludes to Jews.

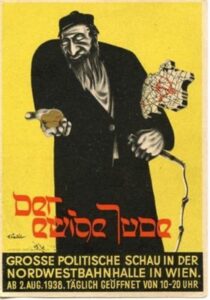

In 2020, Goblincore migrated to the video focused internet sensation Tik-Tok, the well loved successor to Vine, though history continued to repeat itself. A video tagged #goblincore appeared on the For You Page over quarantine. In it, a young boy dressed up as a goblin, with green skin, pointy ears, a handful of coins, and lip synced to the trending audio sound “If I were a rich man, Ya ba dibba dibba dibba dibba dibba dibba dum.” from the famous Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof. It follows everyday life among the Jewish community of a pre-revolutionary Russian village. A poor milkmann desperate to find good husbands for his five daughters, consults the matchmaker, and also has a word with God. Without any greater context, the audience can only rely upon unspoken connections made between the margins. Very rarely do the margins ever get to say what a full page can. Videos like this one may remain out of sight, never truly out of mind. The handful of coins is an old dogwhistle for anti-semitism, dating back to the popular Nazi-directed film The Eternal Jew. First released in 1940, audiences believed this was actually a real documentary. According to Wikipedia, “The Wandering Jew is a 1933 British fantasy drama film produced for the Gaumont-Twickenham Film Studios and directed by Maurice Elvey. It recounts the tale of a Jew (played by Conrad Veidt) who is forced to wander the Earth for centuries because he rebuffed Jesus while he carried his cross.”

It pertained to a widespread conspiracy about Jewish preoccupation with money. The green skin represents greed. And the musical choice doesn’t exactly make it easy to claim simple coincidence.

The truth is society has always put horns on goblins. Two popular examples highlight Goblins’ immoral values, unpleasant looks, cultural deviations, and general otherness. Christina Rosetti’s famous narrative poem “Goblin Market” tells the story of Laura and Lizzie, two golden haired sisters who find themsleves tempted by the local, predatory goblin merchants. Rosetti’s Victorian era goblins are part-man, part-animal hybrids who possess the combined features of rodents, felines, and birds. The goblins lurk near the river of the sisters house, chanting: “Come buy our orchard fruits / Come buy, come buy” (line 3-4). In response to their chorus, Laura says, “We must not look at goblin men,. We must not buy their fruits: Who knows upon what soil they feed? / Their hungry thirsty roots?” J.K. Rowling’s famous Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone wrote a similar script. Upon his first visit to Gringotts, the literal Goblin controlled bank of the Wizarding World, Hagrid tells Harry “Clever as they come goblins, but not the most friendly of beasts. Best stay close.”

Likewise, a main aspect of goblincore involves the hoarding of “shinies,” usually coins, crystals, any small object worth monetary value. At a glance, the idea seems fun, silly, even harmless, however many remain blissfully unaware of its connections to an ancient antisemitic conspiracy theory concerning Jewish control over international finances. One Tumblr user was accused of being anti-semitic by a Jew, and responded with a loosely paraphrased version of “I’m not antisemitic. Goblins are fictional characters from Europe. My interpretation of them doesn’t mean I hate Jews. Besides, it’s just fantasy.” A few possible solutions come up in response to the problematic associations attached to the group. Either a) simply change the current name to gremlincore, crowcore, cryptidcore, etc or b) give goblins a modern renaissance, digitally baptize their Jew-related sins away. Thus raises the quintessential paradox of Goblincore: is it possible to reclaim goblins without all of their uglies? We have to accept it, sure, that doesn’t mean we can’t change the narrative.

For me, at least, the real charm of goblins comes from their ability to teach us how to accept the parts of ourselves that no one else finds pretty. I stumbled upon Goblincore in 2018, on social media’s resident bastard child, Tumblr. As I scrolled through countless accounts dedicated to moss, mud, and mushrooms, written in a new dialect inspired by deliberately improper grammar, (and badly coded Yiddish), I felt an inexplicable desire to run away into the woods, forget society, and never look back. Either I was deeply in the closet, undiagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder, and desperate to survive my perpetually confusing teenage years, or goblins gave us explicit permission to dig up our unexpressed emotions, which, according to Sigmund Freud, once buried, “will come forth later in uglier ways.” Goblincore said bring me your anxious, your tired, your depressed, and let’s dig up sheer nonsense onto viral typo riddled shit-posts together. The freedom to act completely ridiculous seemed inclusive compared to the real world, where my offbeat humor, nonexistent fashion sense, and quirky habits cast me out of neurotypical realms. This hidden feral landscape offered a welcome invitation to abandon the ordinary. Far too often we are left alone with our own uglies, probably because we’ve always been taught to hide them.

For me, at least, the real charm of goblins comes from their ability to teach us how to accept the parts of ourselves that no one else finds pretty.

We live in a world obsessed with the singular goal of achieving beauty in everything. We want the warm crystalline waters of Caribbean islands, not bone-chilling murky ponds we’ll regret not diving into once we leave. No matter how much we might try to chase it, beauty will always fade before we feel like we deserve it. We tend to believe that once we are beautiful, we are loved. Maybe it’s not really beauty we’re after, but the unconditional approval to exist just the way we are.

Present flaws aside, the initial premise of Goblincore sought to show us that dirt deserves the same appreciation we give mountains, the same way our flaws deserve the same awe we give to others’ perfections. The forest accepts me with my mismatched socks, my acne scars, my oddities.

Why should it matter then, when people don’t? Unlike most of us, goblins haven’t changed much since the fourteenth century. They emerged from the cavernous depths of prejudice into an unashamed icon for outsiders. Goblins don’t care what anyone else thinks, and neither should we.

It’s a daunting endeavor, certainly, to take up space in a story where you know the author will never see your beauty, smiling because you’re happy only to end up described with crooked teeth and evil eyes. Others may appear effortlessly pretty, but the journey to self-worth beyond traditional beauty is a necessary odyssey, even if you need to welcome the monster in the mirror to reach your destination.