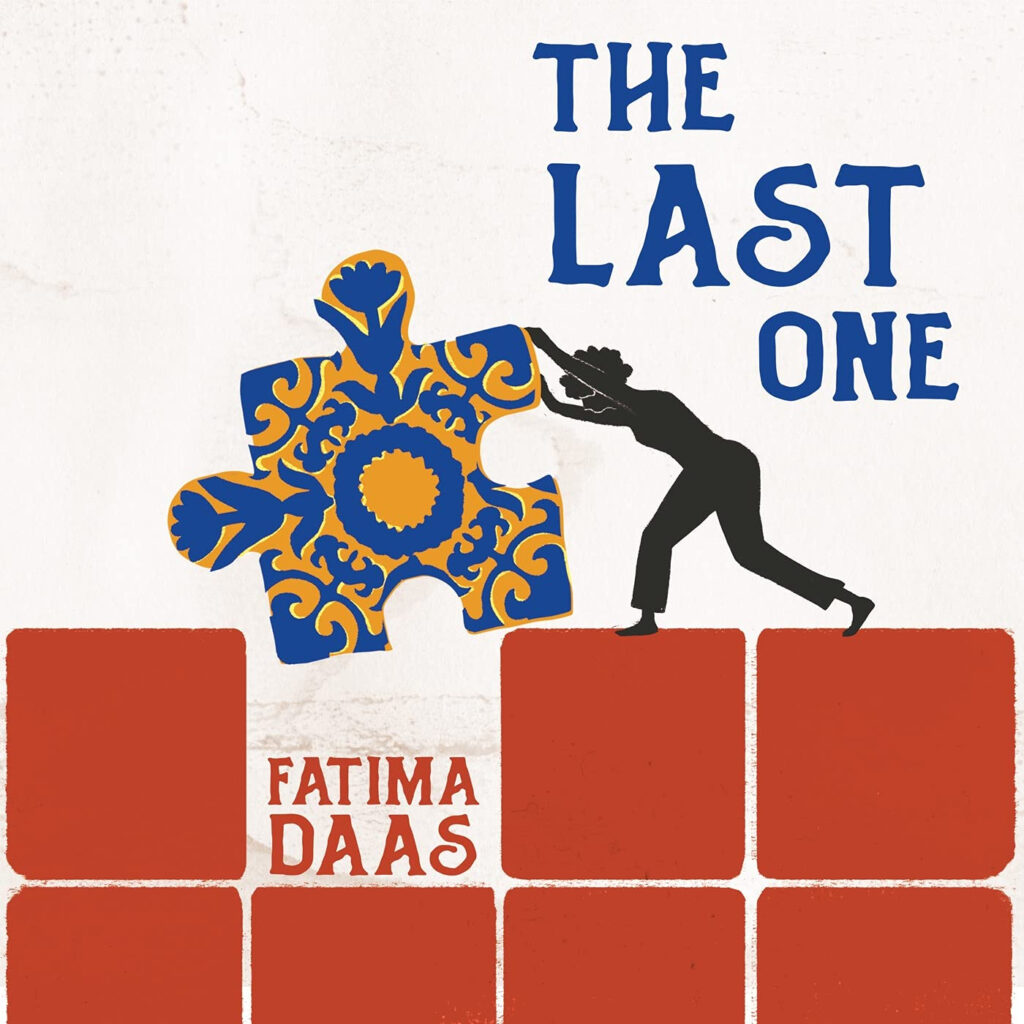

The Last One by Fatima Daas is an ambitious work of autofiction, covering a young woman’s adolescence with chronic asthma and her development both as a practicing muslim and a lesbian in the suburbs of Paris. Originally titled La Petite Dernière, this translation by Lara Vergnaud is the English launch of a debut author in the French literary scene. Daas has gained a large amount of attention and acclaim within France due to her propensity towards writing taboo in all its forms, including blurring the lines between ethical inclusion and what is honest in literature. With this piece of autofiction she reaffirms both her identity as a lesbian and as a muslim together, and chronicles her shifting understandings of her family and her own future as a writer.

Daas reintroduces herself on nearly every page, expanding on her name itself throughout the book and it’s holiness in comparison to what she sees as her sins. The dynamics of Islam and how her name has been inherited are very compelling within her prose. The portrayal of the name Fatima as something that binds, a woman’s identity being inherited, is able to bring some of the fragments of chapters together.

However, Daas’s fragmented prose is originally well done but overly present. While her flat tone is a distinct voice, it becomes forward to the point of being disjointed. It states without effectively creating resonance, and moments of action and character movement are compelling, but so sparse between pages that it becomes difficult to find any forward momentum.

It is also, despite its advertising, not a love story.

Nina Gonzales takes up all of nine pages within the novel. The other dozen or so pages in which she is referenced are comparisons, wishes, and fleeting thoughts of desire within Daas. Nina is more of a device throughout her hook-ups, used as a reflection of Fatima’s own desires; Cassandra is younger, Ingrid is more demanding, Gabrielle can’t capture her attention the same way. More notably one of her most distinct wishes, while reticent, is to not be written about.

“Since meeting Nina, I’ve written every day.

I scribble bits of sentences about all the women I compare to her, all the women I can’t love.

Silence.

I look at Nina. I ask her if I can write about her, explaining that it’s important to me that I have her consent.

She hedges, as she often does when I ask her something.

When she’s not hedging, she doesn’t answer at all. Or else she makes a joke or quotes some complicated philosophical saying that I can’t figure out.

I get a telephone call, so we don’t finish the conversation.

I think about it several days later but don’t dare bring it up.

I think about it every time I see her name take shape on the white page on my computer.”

Autofiction is almost designed for this type of blurring between the author’s ownership of experiences and the people that they know. There have been many conversations recently of fiction that uses elements or entire identities of other people. Most controversial was the popular “Cat Person” by Kristen Roupernian, and the resulting essay “’Cat Person’ and Me”. In the current literary scene, we have been asking more and more questions as to what is moral of our prose. Daas’s bravery seems to extend to the newly established taboo of direct inspiration by incorporating Nina and her reluctance to be written, for Daas’s work seems to refute silence.

Despite the faults within her prose, Daas most certainly deserves credit for her bravery. An immense amount of queer muslims face shame and degradation for publicly coming out; to reaffirm that she is both muslim and a lesbian is something that puts her at the center of a large controversy. Most notable is her incorporation of prayers within Islam, pages apart from her descriptions of loving another woman. It is perhaps the most engrossing part of the book, to watch someone reclaim their faith over and over again.

“My mother says you’re born Muslim.

But I think that I converted.

I think I’m still converting to Islam.”

However, the work almost becomes dependent upon her bravery, as if the facts of her life are enough to make the entire novel. While interesting, the repetition is unable to recast images and identities into something that fully resonants as prose. The novel’s structure itself continues this pattern as paragraphs are often traded for sparse sentences. It is intentionally a fragmented novel, but true scenes are far and few between. It seems elementary to harp back to show not tell, but also necessary. Where Daas tells us everything we could want to know about Fatima, we are never able to fully be a part of her world.

Maybe that’s a limit of autofiction, understanding just how incapable we are of writing our own worlds completely. More than that, maybe we understand that there is no way to invite any number of strangers into our homes without taking precautions. Her work has received many glowing reviews, most of which I disagreed with. Still Daas’s work has continued to enchant, and her warm welcome into the French literary establishment signifies that they are seeing what many others know to be true: Daas is a writer willing to step into the light.

Dilara Sümbül is a writer from San Francisco. She is the founder and editor-in-chief of Flat Ink, an editor at Dear Asian Youth, and a reader at Farside Review. She loves all forms of experimental, magical realist, or horror fiction, and more of her work can be found at dilarasumbulwriting.com.