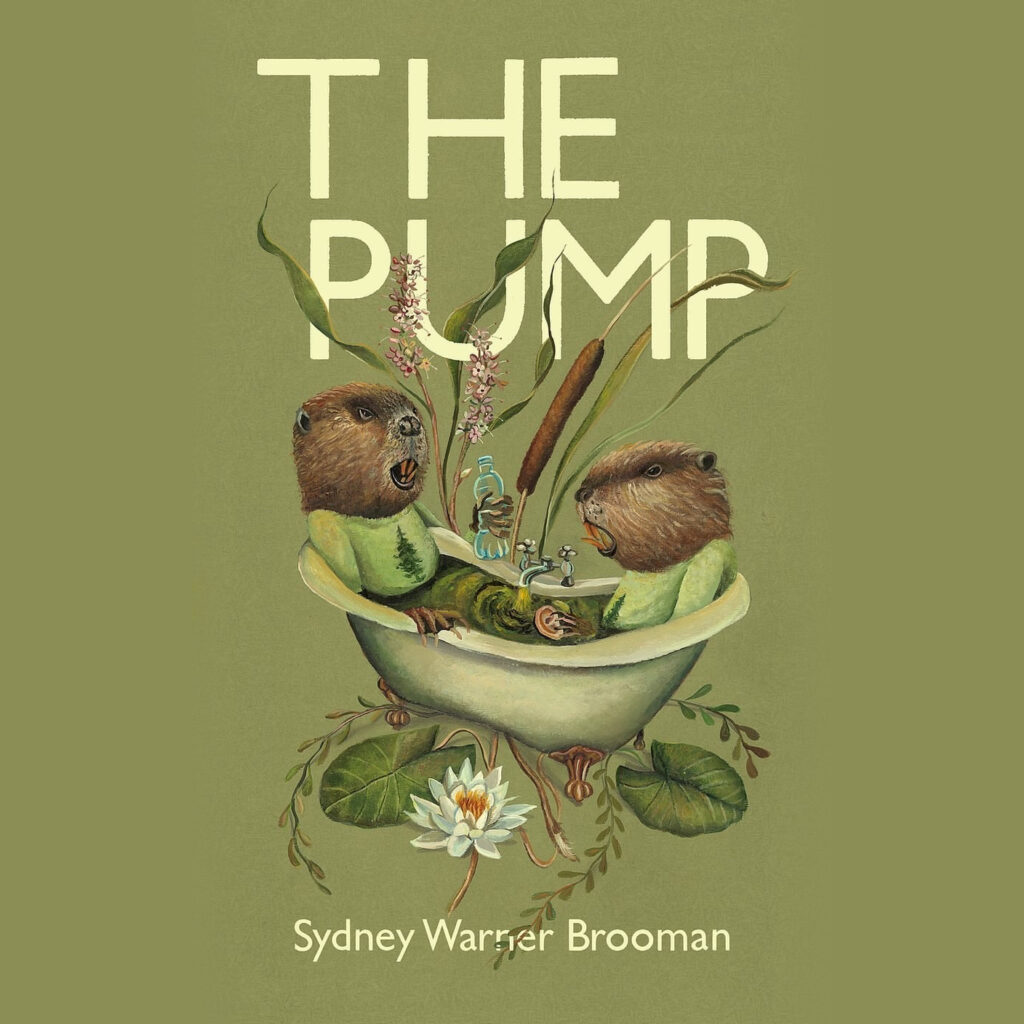

With their debut short story collection The Pump, Sydney Warner Brooman (Invisible Publishing) hosts a gothic welcome party for readers from the striking first line: “Your mother does not want to move to The Pump,” and delivers until the end.

Carnivorous beavers, art-eaters, and a mysterious illness take over a small southern Ontario town in Sydney in this Canadian reckoning that seamlessly weaves together horror and reality. An old woman grapples with the consequences of age and marriage after a stray cat appears on her front porch. A young girl hunts beavers with her father only to discover something far more sinister. A rash causes people to compulsively write words on their skin and makes two girls question whether great art really does warrant great suffering. Adults play a deadly version of the childhood game “Grounders.” Brooman brilliantly explores themes of intergenerational trauma, queerness, mental health, and intimacy through fiction. Yet rather than direct characters so they can show us their world, Brooman pulls us into this experience with the second person limited perspective “You.”

As I dove deep into the unfamiliar world these narrators beckoned me into, I was struck by the nostalgia I felt over a place I had never been to. I am an outsider to this strange setting, yet I got to know these close strangers like I was, to quote the protagonist from Danny Boy, “rooted deep into the damp Pump Playground.” Like the girls at the gallery who look at paintings of lighthouses, I came for the art, but I stayed for the story.

Welcome to The Pump!

First of all, thank you so much for agreeing to participate in my first interview and congratulations on the publication of The Pump, which comes out on September 7th, 2021, from Invisible Publishing. I’m always curious about how writers got their start. What’s your author origin story?

I started writing creative nonfiction and poetry at a really young age. I made little nonfiction books for my family when I was about seven years old, sharing my “expertise” on different subjects like art and family and dolphin friendly tuna. I wrote my first short story when I was thirteen, for a class project. I got H1N1 (Swine Flu) on my Thirteenth Birthday and had to stay home from school for a few weeks because my doctor thought I might actually die. When I got back to class, my teacher told me to write a story about anything I wanted as a make-up assignment for what I’d missed while I was gone. I wrote a story called “No Rules” about a Ferris Bueller-esque student who turns his elementary school into a water park. My teacher liked it so much that he tacked it to the wall outside our classroom. After I wrote that, I couldn’t imagine myself doing anything else.

The Pump takes a small town in Southern Ontario, Canada and gives it a delightful gothic renovation. Are there any memories in particular that inspired you to transform a familiar place into such an unusual, nightmarish setting? Also,were carnivorous beavers involved?

Every single story in The Pump has a handful of memories from my childhood and adolescence. Some events are depicted in a literal way, like “Danny Boy”, which came about because of my experience with Pica and witnessing the aftermath of a train accident when I was young. The salt dome and the church camp and the pumphouse from some of the stories are all real places I had real experiences in. Other things in the book are larger metaphors that stem from the emotional experience of certain memories, like the writing sickness in “Vellum.” No single story is a direct reflection of my life though–I wouldn’t be able to point to any one character and go “that’s supposed to me.” Eloise from “Vellum” or Laurent from “Max Aux Dents” probably have the most of me in them. One of the only elements of the book that isn’t taken from my life is the beavers. They just seemed like the perfect animal in this instance.

Did you intend to write a collection from the start or were the pieces written individually with similar themes? Was it difficult to put them in order?

I wrote the first drafts of The Pump as a fourth year creative writing thesis project at Western University in London, Ontario, under the supervision of my mentor Tom Cull, the former Poet Laureate of London. I knew that I wanted to write a short story collection before I even knew what it was going to be about, so the basic structure was always there. With each draft, the stories became more and more interconnected, and it took me a couple of years to realize that the book was less a collection of stories, and more so one narrative, separated into different perspectives. The chronological order of the interconnected details ended up dictating the order of the stories more than anything (how old certain characters were when certain events occurred).

Your work often tows the line between horror and surrealism. Do you think these elements of fiction allow you to explore your own fears as a queer, nonbinary person with a broader audience?

My short answer is, sort of. I definitely think that I use the surreal elements of the text to explore my fear, but I see that fear coming more so from my perspective as a traumatized person, and less so as a queer person. So much of the queerness in The Pump is there simply because I am, in a lot of ways, telling a story of my experience, and as a queer person, my experience is going to be queer. I didn’t set out to write a book with as much queer representation as it ended up having– it happened largely by accident. I think that’s one of the loveliest and most important things about letting marginalized writers tell their own stories: the representation often just happens naturally, in a way that isn’t forced or inaccurate. The book I’m writing now doesn’t have as many queer characters as The Pump does, and that happened by accident too. Sometimes I writing directly about my queerness, and sometimes I’m not, but I’m still a queer writer regardless.

The Pump exercises a lot of experimental techniques, like word repetition, the use of brackets, the absence of quotation marks in dialogue, and the second person point of view. What excites you most about language and form as a writer?

I get a lot of questions about the quotation marks. I don’t put quotation marks in any of my published work, and admittedly, it’s just an aesthetic choice. The other elements of my style–the brackets and repetition and different structural things– come from a few different things. I write poetry as well, and poetry has really given me the license to play with form in a way that feels less restrictive than traditional prose. After writing poetry for a couple of years, a lot of the techniques I was using bled into my fiction in a way that I enjoyed. I can’t write a single prose sentence anymore without thinking of its cadence and musicality. I read everything I write out loud before I send it off anywhere because the sound of my writing is important to me. Another part of it is that I grew up with a really severe stutter and verbal motor tics. I figured out pretty early on in my life that in order to share my work with people, I needed to manipulate it in ways that helped me read it out loud– ways that other writers didn’t have to manipulate their work. In everyday life, my vocabulary has a lot of transition words that I use to carry me from one part of a sentence to the next, in order to avoid words that start with letters that my stutter can’t get through. Tay’s narration in “Mal Aux Dents” only has the word ‘like’ in it so many times because it makes the story easier for me to read. I created the entire character around that element. That level of manipulation is what excites me most as a writer — telling the story I need to tell, regardless of whether or not I’m following the rules.

In a blurb, you were compared to both Shirley Jackson and Alice Munro, whose quote you used as an epigraph. How do you feel about that?

Stressed! It’s accurate thematically and stylistically, but they are, like, them, and I am, like, me.

If you were stuck on a deserted island and could only bring three books with you, what would they be?

Danny The Champion Of The World by Roald Dahl, The Lonely Hearts Hotel by Heather O’Neill, and The 1962 Book Of Common Prayer.

Anything else you would like to add? Anything we missed?

I mean, no one ever asks me questions about my French Bulldog Sloan, who is named after Ferris Bueller’s girlfriend in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. She steals underwear and hides them around the house, in case people were wondering.