Electra Heart wastes no time introducing herself.

The album begins at an almost-climax, rock-guitar strumming and synthpop beats swirl together to form the opening single Bubblegum Bitch, a lyrical thesis statement of what’s to come. A theme-song with manicured claws behind it, she is brash. She knows exactly what she wants, and as the instrumental swells behind her, we know she’s going to get it. An invocation to her inner muse, she tells us “welcome to the life of Electra Heart!”

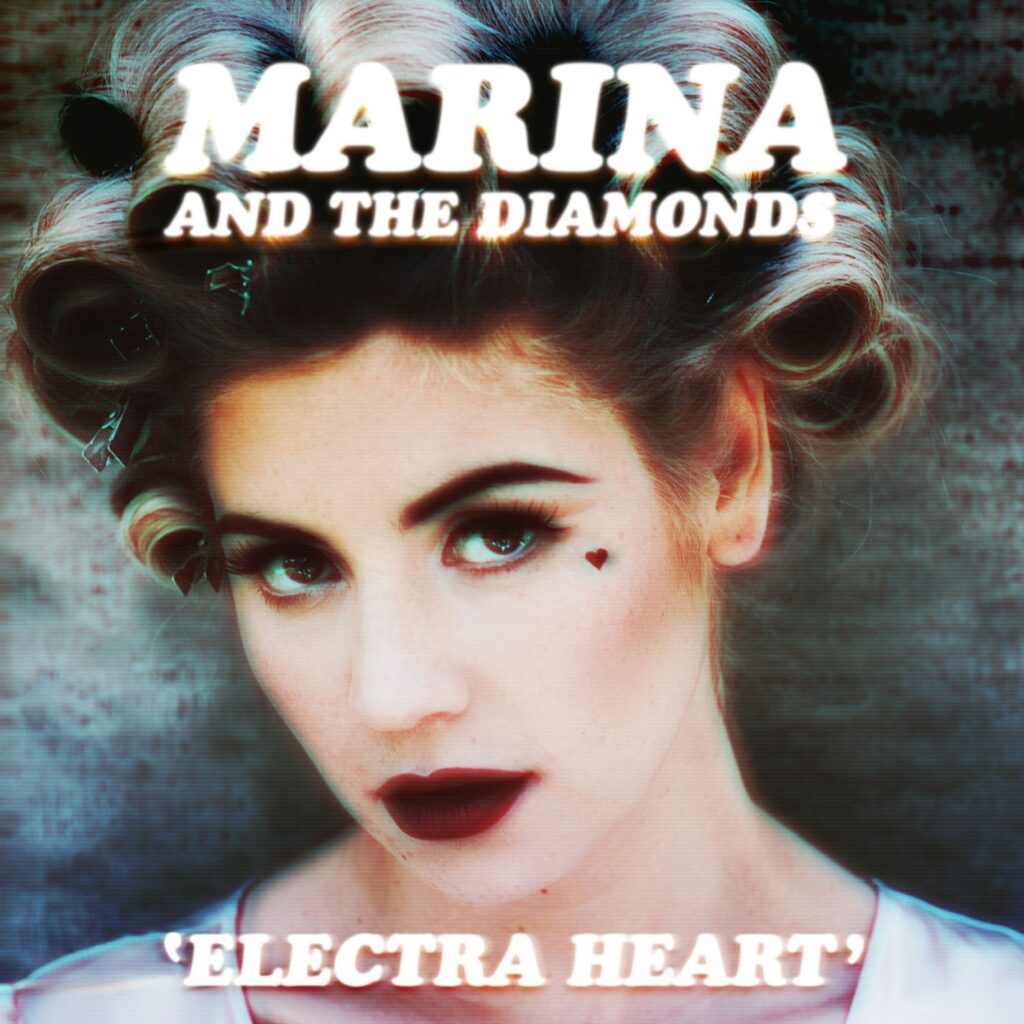

I was a middle-schooler when I discovered the album, a conceptual record released by burgeoning indiepop star Marina Diamandis in early 2012, and immediately sensed that it was the coolest music to ever exist. Electra was the ultimate act of play-pretend; she was larger-than-life to the point that she required taking on the aesthetics of multiple women, sugar babies and stepford housewives and vengeful divorcees. She bleach-dyed her hair and stenciled hearts on her cheek. She sampled quips from Valley Of The Dolls and the flirty greed of Madonna’s Material Girl. She released an eleven-part music video series outlining the birth and death of Electra Heart, a living experiment on the vagaries of womanhood in all its campy excess.

She was a tragicomic, a lifeforce bursting within a cocktail dress. I was obsessed. According to Spotify, I was one of Marina’s top 0.5% of listeners the year I discovered her. I made fancovers and hyper fixated on the (very sparse) lore surrounding Electra Heart, demo tracks and music-video analysis. I was closeted at the time, struggling to exist within the harsh identity formation of adolescence. I was gawky; I wore velcro-crocs and hid in the back row of every classroom. I was nothing like the person I wanted to be. And Electra, for all her faults, was everything she ever wanted to be.

She was a tragicomic, a lifeforce bursting within a cocktail dress.

Electra Heart was a wild departure from Marina’s previous works. Her debut The Family Jewels marketed the singer as a slightly more danceable Kate Bush, piano trills and howls backed by exuberant instrumentals. She growled and staccatoed and wrote scathing diss tracks involving Kermit The Frog. She was always performative; her initial stage name was “Marina and the Diamonds”, almost-implying a solo artist so grandiose she can be believably described as an ensemble. To clarify, Marina and the Diamonds was not a character or an alter-ego. She wasn’t an exaggerated version of the self, rather the self was just exaggerated. But Electra Heart was a character, a hyper-stylized and narrativized performance of femininity. Marina ditched the trills for slick production, a glossy tribute to pop womanhood. More than anything, Electra Heart was an aesthetic experiment, the album equivalent of a dress-up doll.

The critical response was tepid. It’s true; the constant allusions and archetypes can sometimes feel hammy rather than impactful. Laura Snapes of Pitchfork writes that throughout her listen of the album, “there was very much a feeling of Marina overcomplicating the whole affair.” Beneath the ambitious music video series and half-hearted references to Greek mythology (I can’t even begin to defend the odd misspelling of Hypocrates), many critics worried that there was little of substance left. Alexis Petredis of The Guardian writes, in what I believe most sums up the critical response to the work, “I wonder what might have happened if Diamandis had not worried too much about becoming everything she isn’t.”

But what’s so awful about wanting to be someone you aren’t?

Electra Heart is campy, melodramatic. It tries just a little bit too hard. But that’s what we loved about it. The album amassed an online fandom, comprised mostly of young, queer fans. We made fancams and mashups and created the sparse lore we would obsess over. It was a form of idol worship, a recognition of the fascinating extensions of self that Diamandis created.

Critics claimed the work valued form over function, aesthetic over substance. But maybe the aesthetic was the substance. It’s no coincidence that works like Electra Heart spoke to queer audiences, why it remains the musical equivalent of a camp classic. The queer experience is rooted in the deconstruction of identity and alter-ego, especially within the context of gendered performance. To exist as a member of the LGBTQ+ community is to be subject to uncomfortable social regimentation, to be told that one cannot be who one really is. So of course, we worry over becoming everything we aren’t allowed to be.

The cultural definition of queer expression stops mostly at Rupaul’s Drag Race or Queer Eye, but the queering of aesthetic expression goes deeper. If drag is the pursuit of stylized gender performance/alter-ego to create a heightened version of the self, then is Electra Heart not drag? I fell in love with Electra Heart before I knew anything about drag beyond John Travolta in Hairspray. And I think that’s the real value of the album; it modeled how one can exaggerate the self to become the true self, how identity can be artistic performance.

The queer experience is rooted in the deconstruction of identity and alter-ego, especially within the context of gendered performance. To exist as a member of the LGBTQ+ community is to be subject to uncomfortable social regimentation, to be told that one cannot be who one really is.

We have this pervasive idea of authenticity as stripped down and raw. But Electra Heart is melodramatic, more grandiose than it really needs to be. And yet I still saw myself within it.

Marina Diamandis has since sided with the critics, disavowed every alter-ego. Her current body of work is less pop-synthetic and more black-and-white candid shots. The musical equivalent of a makeup wipe, she’s revealed the real Marina under all the frills and glitter and stenciled-on hearts. It’s our unflinching dedication to the real, the unadulterated and unobfuscated, that worries me so deeply. It’s limiting. It’s reductive. It prevents exploration. As a closeted kid listening to Electra Heart, I did not define realness as what I was, but what I could become. For me, there was nothing more authentic than answering the question: “If I could transform into anything I wanted, what would I be?”

My answer? To quote Electra Heart herself:

“I’m gonna be your Bubblegum Bitch!”

Christian Butterfield is an 18-year-old poet/essayist/totebag-enthusiast from Bowling Green, Kentucky. In 2019, he served as the National Student Poet of the Southeast, and his work has since been published/recognized by Best Teen Writing, the YoungArts Foundation and The Adroit Journal. He reads for EX/POST Magazine and was a 2020 Adroit Mentee in Creative Nonfiction.