Danae Younge is a four-time award-winning poet and an editor for Kalopsia Literary Journal. At twenty, Danae’s work has been internationally recognized by over forty publications, including Petrichor, Bacopa Literary Review, and Driftwood Press. She was a winner of National Poetry Quarterly’s annual contest in 2020 and placed in the It’s All Write competition. Her flash fiction piece, “Skeletons Don’t,” was longlisted in Grindstone Literary’s international competition. Melanin Sun (—) Blind Spots is her debut chapbook, and her second collection is currently in the works. Her poem, “the moths are out, so close the window,” was published in Issue II, and you can find her on Twitter @danae_younge_.

For Danae Younge, dreams do come true, even if they were formed in kindergarten. In conversations on her debut chapbook, Melanin Sun (—) Blind Spots, she speaks fondly and introspectively of embracing uncertainties and not knowing. As she explores deeply sensitive and controversial themes like race, grief, and identity, she alludes to readers the need to let go of the expectations to know it all and to instead acknowledge their blind spots and limitations.

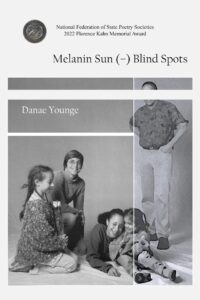

Melanin Sun (—) Blind Spots is the 2022 Florence Kahn Memorial Award Winner of the National Federation of State Poetry Societies’ College Undergraduate Poetry Competition. Through this collection of ten poems, Younge intertwines the passing of her father with her leanings on race and heritage through his eyes, exploring how this familial loss brought on a disconnectedness from the identity she had always known as a biracial black woman. As Younge continues to find new understandings of her racial identity, her poetry highlights how she learned to embrace not always having answers.

Congratulations on winning the National Federation of State Poetry Societies College Undergraduate Poetry Competition and, of course, the publication of your chapbook. This is huge. How do you feel about this accomplishment?

Yeah, it’s insane. Even though I definitely wasn’t expecting to win, I thought I had a real shot in the competition because I did craft this micro collection specifically for this contest, so I was really hoping that it would work out in the months waiting for the results—but it still is and was incredibly shocking when I got the acceptance email. It’s just a very bizarre feeling. I’ve dreamed about having a published book since I was in kindergarten, and I even remember I made these homemade books, stapled together, and imagined them being in the library. So, yeah, it’s unreal.

Was your experience writing this collection different from your previous works, and if so, in what ways?

Yes. As I mentioned before, I crafted the whole thing for this contest, so it was very different. I’ve never sat down to actually write a full collection, or in this case, a microcollection specifically to be one cohesive piece. I’ve always just written individual poems, and the reason I did this is because the contest actually had guidelines where the poems you submitted had to be not out for review and not previously published. So, I was kind of forced to approach it in this way. And I’m so grateful for that, even though at first I saw it as kind of an inconvenience. I’m so grateful that they had this guideline because I think, in the end, it made the chapbook much more cohesive as one entity. And I also had fun sprinkling in recurring imagery and metaphors across different poems, which is something that’s not possible when you’re writing a singular poem. And then with the strikethrough and redaction, those were motifs throughout the collection that, again, otherwise were not possible in one poem.

I’m really glad you brought up the strikethroughs and redactions, because I found them really interesting while reading. From the title of this collection to the body, you give your audience ample room to finish your thoughts and prompt us to really reflect and form meanings for ourselves with your use of strikethroughs, block outs, redaction, and overall writing style. Was it important to you that readers be able to deduce meaning and find relevance for themselves? Why was that?

I definitely think that it was important to have people reach conclusions on their own. I wanted the poems to be applicable and relatable to anyone who had struggled to self-identify. So, by leaving those labels incomplete and leaving those sorts of words redacted and using strikethroughs, I hoped it would give the reader space to kind of reflect on their own blind spots so that it gives them this freedom to kind of relate to the piece more. Even if things are redacted, they can try to project their own answers onto that. But then, even more important to me was to accept that you’re not always going to know the answer, and specifically when it comes to identity—racial identity, heritage, sexuality, things like that.

In Melanin Sun (—) Blind Spots, you start by exploring the loss and grief of your father, and transition to racial prejudices and the quest to find self, while also giving us historical context. What was the process of putting this collection with these types of themes together like?

I knew I wanted the chapbook to focus on how my understanding of my own racial identity past the biracial label blurred as more years passed since my father’s death. And according to anything I’ve ever been told about race, the way it defines us in the modern world is largely linked to history. And though one’s parents and the history of a larger group of people are commonly thought of as large influences on racial identity, I myself have never fully been able to grasp all the specific ways in which they impact my movement through the world as a woman of color. And because of this, putting together the collection was a struggle at times because I would put two poems side by side on the page and not always know how they connected. Even though I knew that there was a connection. So that’s when I often turned to the redaction and the strikethrough as a place where I could accept and embrace that uncertainty.

What inspired the title, Melanin Sun (—) Blind Spots?

The sun is often an emblem of life and enlightenment. So, Melanin Sun is kind of representative of me, claiming and discovering my identity through these poems. But the collection, as I mentioned before, also relies on the honesty of not knowing things. So, it was vital that the title reflect my own blind spots, things that I am not aware of, things I don’t know; and then the little symbol in the middle, I interpret it as a minus sign, so it’s subtracting the blind spots that I don’t see. But I think it’s wonderful that people can interpret it in their own ways, as we were talking about before.

You are often introduced as a biracial poet, and one of the recurring themes in this body of work was your identity as a biracial person and your journey to owning it—from “Just a Brown Girl’s Glass Box” to “Fish Eye” and “Alibi.” Did you intend for it to be that way—to be introduced as biracial, and why was it important to show and own your identity as biracial in this collection?

Yeah, it’s funny that you asked that, because I’ve always kind of felt unsure about whether or not to include my biracialism in the author bios that I send to publishers. It seems like the right thing to do because it seems like it is, or at least it should be a big part of what shapes me as a person. But not knowing how exactly it has shaped me has caused discomfort in my life. So, I’ve always felt a little conflicted when including it in my bio, something that is meant to represent relevant information about me as a writer. So, when I decided to write a body of work that is specifically made for exploring this discomfort, showing my identity and claiming it, owning it was absolutely crucial. And so, I was finally pushed to sit with it for a long period of time. Writing Melanin Sun (—) Blind Spots has been the first time that I’ve felt truly at ease when I’ve released a piece of writing to the world that included my biracialism simply because it allowed me to be honest with myself and honest in admitting the unknown and admitting my own blind spots.

What was your favorite aspect of putting your chapbook together? Do you have a favorite poem from this collection?

I think my favorite poem from this collection has changed multiple times. That kind of answers the first part of this question, in that I just loved the experience of going through and writing each poem, piece by piece, and knowing that they specifically related to the others and depended on the other poems, like a car tower, you might say. I think my favorite poem from this collection, at first, was “Alibi,” because of the freedom I felt when I wrote it. I was able to admit this discomfort and the guilt that I sometimes feel whenever I remotely attach myself to a racial identity, because no matter what, it always feels like appropriation in some way. In that poem specifically, I talk about my sister doing my hair using hair that she bought at the store—specifically a store for black women, and in that moment, I felt like I was appropriating black culture even though I am black, and that’s just how I have dealt with my racial identity and the struggles I’ve had with that. Recently, it’s kind of changed to “Catfish” because it has similar themes, but it is within the context of body image and captured in a shorter poem.

What do you hope readers will take away as they read this collection?

I think that it’s okay to not have the answers, particularly when it comes to aspects of identity like race, sexuality, and heritage. So many important artistic works emphasize and celebrate confidence when it comes to these topics, and that’s absolutely crucial and so important. But I think we should also celebrate and embrace uncertainty when it’s there and not place an expectation on people, specifically minority groups, to have all these answers.

You can read more of Younge’s writing at danaeyounge.com.

Tarinipre Francis is a Nigerian writer and budding journalist who delights in exploring views that are often muffled and speedily forgotten. She is spurred by her environment and believes that the writer does not choose the story, but that the story chooses them, so she allows herself to be led by stories. She previously worked as the Communications Officer for AWWAS and H2H Photography, sister organizations that sought to combat the culture of silence surrounding abuse by assisting victims of abuse in finding healing through creative expression and telling African stories through photodocumentary, respectively. She currently works as a freelancer and ghostwriter, and publishes her works on Medium when she finds the time. You can find some of her work on Medium.