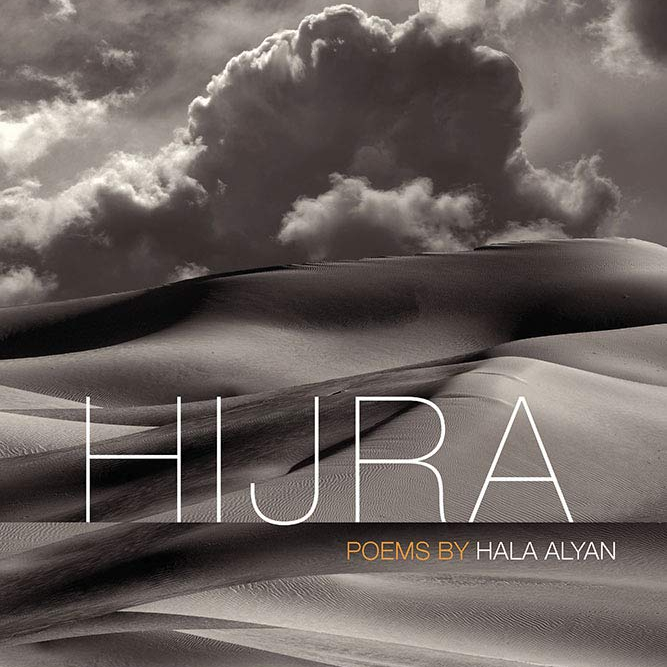

Stories of migration are retold through the eyes of daughters, mothers, sisters, wives, sacrificial gazelles, a queen Cassiopeia, and beyond. Hala Alyan’s third poetry book, HIJRA, places womanhood at the core of reconciling resettlement and selfhood.

The collection is titled after the Arabic word for migration, hijra, which also directly refers to Prophet Muhammad’s religious migration from Mecca to Medina. Hala Alyan uses this notion of admirable and holy journeying as the story of her people: migrants of the Middle East, particularly Gaza and Syria, who are forced to flee their homes in a transnational voyage. Through this, Alyan gives voice to the subjugated, reclaims the position of the oppressed and turns it into a championing of what it means to be a female exile in the homeland, during migration and after re-settlement in foreign lands. The idea of exile has always been key in Middle Eastern poetics, where narratives of diaspora, occupation and estrangement have counted for a significant portion of literature emerging from the area.

Through the poetry collection’s apocalyptic magical realism, Alyan explores the liminality of identity and the need for endurance following displacement. As a Palestinian-American woman, the poet’s home was ever-shifting throughout her upbringing. An individual of the diaspora, Alyan grew up in Kuwait, Oklahoma, Texas, Lebanon and Maine. This familiarity with displacement and its effects on identity are tangible in her poetics, centering the exilic feminine as the witness, storyteller, and listener of this collection.

Split into four main parts, the collection acts as a journey through time, and we witness the unquestionable overturning of normal life. Through this, Alyan offers a redefining of personhood and, as a result, womanhood. Part Two of the collection features fifteen poems, each titled after an Arabic woman’s name. Whether these names refer to real people in the poet’s lives or not, they resonate with Arab readers in their familiarity and emphasize the importance of the individual identities of women. There is a collective voice and address that runs throughout, mimicking a universal testimony shared amongst exilic and diasporic women.

Even in its earliest intimations, the notion of self-sacrifice presents itself as potent and palpable, a theme which carries on throughout the collection. There is a certain sacrifice expected from the bearer of tragedy. In this collection, this falls upon the shoulders of the women who are depicted as the backbone of Arab communities, and simultaneously custodians to their suffering, as evident in Before the Revolt, Seham, and Amna. Before the Revolt reads: “Our husbands cut steel. We suffered their bodies, / held our thighs apart like wings.” Still before the unfurling of crisis, the feminine identity was still tied to notions of altruism and bearing of suffering. However, even this sacrifice is counteracted with power and a reclamation of honour. The women in HIJRA are strong and resilient. They are outspoken and adaptable, and they carry this power across generations, borders and timelines. In Asking for the Daughter, the poet writes: “Because a woman / who knows war knows deliverance, her mouth a sea / of sharks trapped in coral.” The women in these poems are filled with desire to survive. Desire is not a topic that is shied away from, and instead the suffering experienced by these women on their journeys is turned into their own source of control and reclamation of honour over their lives and their bodies.

The collective feminine voice in HIJRA shows us that writing on exile is not only a way of lamenting what has been lost, but also as preservation of history and narrative. HIJRA is a testament to selfhood and existence. It is a tribute to the overlooked voices of exiled women, and a platform to ensure the perpetuity of their lives and stories.

Reena Bakir is a writer from Amman, Jordan currently pursuing an MA in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway University of London. Mainly focusing on poetry and fiction, she is the Literature Editor at The Orbital and a regular article contributor to online publications such as Snippets Mag, where her poetry has also been featured.